As the first in a series of public oral histories at The Curran Homestead, author Wilbur Wolf, of Orlond, ME, will be offering signed copies of his Memoir of a Farm Boy as well as sharing some of its details in this talk and slide presentation at The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum, Fields Pond Rd., Orrington on May 28 at 6:30 PM. Wolf’s book, which was originally conceived as a memoir for his children, documents his family farm experiences in the 1930s and 1940s. Beginning with the almost two hundred year history of his parents’ upstate New York dairy, he offers details of early mechanization, animal husbandry, small town life, and poignant human relations in a rural community of the past.

According to Dr. Robert Schmick, Volunteer Director of Education at The Curran Homestead, “Wolf’s experiences are becoming more unique with each passing day in America as small family farms are consumed by corporate owned agro-businesses and many more are simply re-purposed for residential subdivisions and strip malls. It is not that the times that Wolf writes of were simpler; it is that there was a close knit community on hand to comfort people during good and bad times, people discovered their own entertainments, and there was both a necessity and personal pride in earning a living from the land and ones own industry that is no longer commonplace. There were a greater number of farms per capita in Maine and the rest of the US, and people not only had the ability to grow more of their own food but supply their local community with lower cost staples not tethered to world petroleum prices.”

Schmick added that “it is our mission at The Curran Homestead to preserve the traditions of the family farm, self-reliance, and ingenuity which were part of Wolf’s experiences, and through continued public talks like this we hope to both preserve a bit of this past so that it may continue to mold future generations. Come pick up a copy of Memoir of a Farm Boy, have it signed, and chat with its author Wilbur Wolf. Wilbur may even play a tune or two on one of our early pipe organs after the talk. Coffee and homemade cooked rhubarb on shortbread will be served. Admission is free, but we are an all-volunteer non-profit organization and would appreciate your donations.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

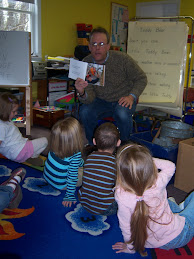

Maple Sap Flows at The Eddington School

Mrs. Diana Higgins’ class at the Eddington Pre-School got a taste of maple sugaring this past Monday , April 13, 2009 when Volunteer Director of Education Robert Schmick of The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum in Orrington was on hand to share the details of the sap to syrup process. A Native American legend that identifies the possible origin of maple syrup in America was shared with Mrs. Higgins’ class along with the process and tools required for harvesting the sugar rich sap from maple trees. The group filed out in a single line to a nearby maple and witnessed the tapping of a tree with a hand brace. A bucket with lid was fixed to a spout for students to check daily on the process of sap flow, which has been considerable even though sap gathering has largely ended in the area. Mrs. Higgins, Teacher Assistant Marie Sekera, and students were given a taste of newly made Eddington maple syrup drizzled over homemade ginger ice cream from Frank’s Bake Shop on State Street in Bangor, which pre-schooler Brian Bates of Eddington commented was “a very good idea.”

The Curran Homestead hopes to tap more trees at the school next year, make syrup out at the farm in Orrington, and provide it for a pancake breakfast for the Eddington pre-school and kindergartners. “This is the first of our developing outreach to area schools,” said Schmick, “and we hope to bring more rural experiences, like maple sugaring, that are among the traditions of our regional identity, to both young and old in our community.” For information about this or any of a number of programs The Curran Homestead can offer to your school or organization in the future, please contact Dr. Robert Schmick at rpschmick1@aol.com, or 207-843-5550.

The Curran Homestead hopes to tap more trees at the school next year, make syrup out at the farm in Orrington, and provide it for a pancake breakfast for the Eddington pre-school and kindergartners. “This is the first of our developing outreach to area schools,” said Schmick, “and we hope to bring more rural experiences, like maple sugaring, that are among the traditions of our regional identity, to both young and old in our community.” For information about this or any of a number of programs The Curran Homestead can offer to your school or organization in the future, please contact Dr. Robert Schmick at rpschmick1@aol.com, or 207-843-5550.

Friday, April 10, 2009

How to Do and Doing as Was Done; Maple Syruping in Eddington

On a little less than an acre on Jarvis Gore Drive in Eddington, ME these past few weeks my four and half year old son Gabriel and I rolled up our sleeves and literally took a stab at 6 or 7 maple trees of varying size (but not less than 12 inches in diameter)tapping them for sap. The practice of tapping trees originated with Native Americans, and once sap was collected in quantity it was boiled to a sweet syrup. Many believe that Native Americans used the sap to flavor meat and other things; the cooking brought out the full sweet taste of the resulting syrup. Euro-Americans came up with the use of indulgent quantities of syrup for their flapjacks, waffles, and everything else that tastes good with it. William Cooper, the founder of Cooperstown, initiated maple sugaring as a commercial enterprise in the late eighteenth century in Western New York. I have been told that local Maine Indians tapped Beech in addition to maples of all varieties and Box Alders too. For the purposes of my own recent maple sugaring venture I didn’t stick to sugar maples alone, which are said to have the highest sugar content and hence require less sap for the desired amount of syrup, I tapped all the large maples on my property. These included a number of different types in addition to one or two sugar maples.

Because my son and I have seen trees tapped and sap boiled in recent years as I have made an attempt to have Gabe experience some of the things I experienced growing up in a small town and on the family dairy farm in Upstate New York, we weren’t complete novices. My hometown itself is filled with low mountains, hardwood forests, and largely fallow fields from a one time thriving dairy industry that is, except for a few, now gone. Many of the trees and woods are still there, although much has been bulldozed and built upon in recent decades including my own family farm. The Town of Warwick is only 49 miles from Manhattan as the crow flies lying near the western part of the New Jersey Highlands, a stop on the Appalachian Trail, which any Mainer knows ends or starts close to here at Mt. Katahdin in Baxter State Park. As a Boy Scout I experienced Warwick’s portion of the Appalachian Trail first hand on a 50mile hike in pouring rain to the well known stop, the Delaware Water Gap. There were many shorter trips on the Trail too by Troop 45 that had so much to do with my lifelong appreciation of the woods.

I can’t say that my family ever tried to make their own maple syrup on the dairy farm I spent much of my early life on but as a 5 year old I experienced maple syrup making for the first time in Mrs. Bell’s kindergarten class at Hamilton Avenue Elementary School in Warwick, New York in 1968. The school itself has been re-purposed as a community center ( my own Eagle Scout project involved repairing and painting two classrooms on the second floor for that purpose way back when), but many of the ancient maples on the property that were tapped then remain. Sometime during those important six weeks of sap harvesting Mrs. Bell’s class filed out to an area on the hill above the school where an earlier version of the school had once stood before it was destroyed by fire in the 1920s; its brick footprint is still visible in the grass. Here were two rows of hardwoods that had once marked the entrance to the largely forgotten school. We stood giddily watching as one of the custodians drilled out a hole with a brace and tapped a metal spout (spile) in for the benefit of the class. The drips of the seemingly clear liquid were almost immediate as I recall. I only observed recently that sap has a faint amber hue to it when it comes right out of the tree.

Fortunately, for our own health, we didn’t have to wait in the chilly morning air for the metal pail that was attached to a hook under the spout to fill to a desirable level. Many of the other nearby maples had been tapped days before, their metal pails filled, and a large quantity of sap brought to the cafeteria kitchen to begin the process of boiling sap to syrup long before we paraded out to witness the demonstrational tapping that morning. After we experienced the resounding tap, tap, tap of the sap from the maple into a metal pail, we filed back into school to the cafeteria to witness steam billowing out of the enormous stainless steel pots in the kitchen, and this fact makes me realize now how long time ago that really was because they carried out the whole process on gas fueled stoves that taxpayers never bauked at, for the tradition lasted long after I moved on to middle school.

The expense of gas heat might have been an issue to a few then but today it would simply be cost prohibitive. Accessibility to a wood burning stove makes the process affordable and possible for me in this era of very expensive fossil fuels. It’s no wonder syrup has practically doubled in cost this year because most commercial makers use more expensive fuels than wood to make their syrup. After my kindergarten class gave their requisite number of "oohs" and "ahs," we had a pancake breakfast with homemade, or rather school-made, syrup. It was delicious.

It’s funny how experiences like that stick with you. Many of our memories today are often the result of a remembrance of a photograph or something that we experienced second-hand via television, so it is the recorded image or even the experience of others shared with us that becomes a large part of our memories rather than the pure and first-hand types of experiences like witnessing a tree tapping and eventually tasting the syrup that originated from it, or lacing on a pair of skates and spending several afternoons falling and getting back up to learn to skate rather than spending that same amount of time watching Olympic hopefuls go through their practiced infinitum skate routines. That maple sugaring experience at Hamilton Avenue is one of my earliest and purest recollections because no one to my knowledge ever snapped a photo that day or has ever mentioned it to me in the four plus decades since. I have thought about it treasuring it for its affirmation of my somewhat romanticized notion of growing up in a small town named Warwick just, as I hope, Gabe, my son, rhapsodizes about those early Spring days in Eddington, Maine tapping maple trees sometime in the future.

My stab at making syrup has much to do with my recent work with The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum. Since taking on a volunteer directorship in August, 2008, I have spent much time learning how to do and doing as was done. Most recently, I harvested block ice out on the 95 acre large Fields Pond, which lay directly across from the main house and barns of the farm and museum, using hand tools as well as contributing to our recent annual Maple Syrup and Irish Celebration where we cooked sap on a well-used Wood and Bishop stove in our formally designated “Sugar Shack” using a stainless steel evaporator.

Bob Croce, a board member of the farm and museum, handled the maple syrup demonstration, as he has done now for eighteen years. He taps trees on his own property near Dedham and cooks up some samples of varying amber color to have on hand for visitors to examine at the annual celebration. He cooks up 10 gallons of the sap during the day of the event; consequently, he has been one of my main sources of information for going ahead and doing the process on my own.

Gabe and I tapped a number of trees that by the last week of March were already past their prime as far as sap getting goes; the holes I drilled were bone dry when I pulled out the bit from them. Among the seven maples we eventually tapped, three or four produced the majority of the sap we collected, and these trees included one ancient maple that is close to Jarvis Gore Drive. It, I suspect, is one of the trees that has survived from those that once lined my road from the intersection of the old "airline" road (Rt.9) along Jarvis Gore Drive often depicted in old photographs from the late nineteenth century. New Englanders often planted a pair of sugar maples in the front of their houses in the old days, and the two identical in size maples near my house may also have been the front of the Unitarian Universalist parsonage in the 1850s that stood on the site of my house which was built in 1879.

We collected roughly 9-10 gallons of sap using old galvanized tin pails with fitted lids and cast-metal spouts borrowed from The Curran Homestead. I filtered the sap thoroughly through four coffee filters set inside of a metal colander. There were moths, bits of bark, and dry sphagnum moss in the sap water before I filtered it. We boiled the sap down in some of my late grandmother’s Presto Pressure Cookers (circa 1950s) on top of our wood stove in the living room. It was a fairly simple process that required a little vigilance to avoid burning the sap down to nothing and scalding the pot with carmelized maple syrup. For the most part, I just set the sap on the stove and checked it when I stoked the fire. I got about 10-11 ounces of dark amber syrup for my efforts that tastes just like the good stuff. I plan on keeping the syrup under lock and key until I can make a pancake and waffle breakfast with it this summer when some of my family comes up to Maine to visit. It will be an exercise in self restraint to save the syrup that long; we love pancakes and waffles at our house. My grandmother always said that stuff that you make yourself always tastes better than anything you buy, and she was right.

Because my son and I have seen trees tapped and sap boiled in recent years as I have made an attempt to have Gabe experience some of the things I experienced growing up in a small town and on the family dairy farm in Upstate New York, we weren’t complete novices. My hometown itself is filled with low mountains, hardwood forests, and largely fallow fields from a one time thriving dairy industry that is, except for a few, now gone. Many of the trees and woods are still there, although much has been bulldozed and built upon in recent decades including my own family farm. The Town of Warwick is only 49 miles from Manhattan as the crow flies lying near the western part of the New Jersey Highlands, a stop on the Appalachian Trail, which any Mainer knows ends or starts close to here at Mt. Katahdin in Baxter State Park. As a Boy Scout I experienced Warwick’s portion of the Appalachian Trail first hand on a 50mile hike in pouring rain to the well known stop, the Delaware Water Gap. There were many shorter trips on the Trail too by Troop 45 that had so much to do with my lifelong appreciation of the woods.

I can’t say that my family ever tried to make their own maple syrup on the dairy farm I spent much of my early life on but as a 5 year old I experienced maple syrup making for the first time in Mrs. Bell’s kindergarten class at Hamilton Avenue Elementary School in Warwick, New York in 1968. The school itself has been re-purposed as a community center ( my own Eagle Scout project involved repairing and painting two classrooms on the second floor for that purpose way back when), but many of the ancient maples on the property that were tapped then remain. Sometime during those important six weeks of sap harvesting Mrs. Bell’s class filed out to an area on the hill above the school where an earlier version of the school had once stood before it was destroyed by fire in the 1920s; its brick footprint is still visible in the grass. Here were two rows of hardwoods that had once marked the entrance to the largely forgotten school. We stood giddily watching as one of the custodians drilled out a hole with a brace and tapped a metal spout (spile) in for the benefit of the class. The drips of the seemingly clear liquid were almost immediate as I recall. I only observed recently that sap has a faint amber hue to it when it comes right out of the tree.

Fortunately, for our own health, we didn’t have to wait in the chilly morning air for the metal pail that was attached to a hook under the spout to fill to a desirable level. Many of the other nearby maples had been tapped days before, their metal pails filled, and a large quantity of sap brought to the cafeteria kitchen to begin the process of boiling sap to syrup long before we paraded out to witness the demonstrational tapping that morning. After we experienced the resounding tap, tap, tap of the sap from the maple into a metal pail, we filed back into school to the cafeteria to witness steam billowing out of the enormous stainless steel pots in the kitchen, and this fact makes me realize now how long time ago that really was because they carried out the whole process on gas fueled stoves that taxpayers never bauked at, for the tradition lasted long after I moved on to middle school.

The expense of gas heat might have been an issue to a few then but today it would simply be cost prohibitive. Accessibility to a wood burning stove makes the process affordable and possible for me in this era of very expensive fossil fuels. It’s no wonder syrup has practically doubled in cost this year because most commercial makers use more expensive fuels than wood to make their syrup. After my kindergarten class gave their requisite number of "oohs" and "ahs," we had a pancake breakfast with homemade, or rather school-made, syrup. It was delicious.

It’s funny how experiences like that stick with you. Many of our memories today are often the result of a remembrance of a photograph or something that we experienced second-hand via television, so it is the recorded image or even the experience of others shared with us that becomes a large part of our memories rather than the pure and first-hand types of experiences like witnessing a tree tapping and eventually tasting the syrup that originated from it, or lacing on a pair of skates and spending several afternoons falling and getting back up to learn to skate rather than spending that same amount of time watching Olympic hopefuls go through their practiced infinitum skate routines. That maple sugaring experience at Hamilton Avenue is one of my earliest and purest recollections because no one to my knowledge ever snapped a photo that day or has ever mentioned it to me in the four plus decades since. I have thought about it treasuring it for its affirmation of my somewhat romanticized notion of growing up in a small town named Warwick just, as I hope, Gabe, my son, rhapsodizes about those early Spring days in Eddington, Maine tapping maple trees sometime in the future.

My stab at making syrup has much to do with my recent work with The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum. Since taking on a volunteer directorship in August, 2008, I have spent much time learning how to do and doing as was done. Most recently, I harvested block ice out on the 95 acre large Fields Pond, which lay directly across from the main house and barns of the farm and museum, using hand tools as well as contributing to our recent annual Maple Syrup and Irish Celebration where we cooked sap on a well-used Wood and Bishop stove in our formally designated “Sugar Shack” using a stainless steel evaporator.

Bob Croce, a board member of the farm and museum, handled the maple syrup demonstration, as he has done now for eighteen years. He taps trees on his own property near Dedham and cooks up some samples of varying amber color to have on hand for visitors to examine at the annual celebration. He cooks up 10 gallons of the sap during the day of the event; consequently, he has been one of my main sources of information for going ahead and doing the process on my own.

Gabe and I tapped a number of trees that by the last week of March were already past their prime as far as sap getting goes; the holes I drilled were bone dry when I pulled out the bit from them. Among the seven maples we eventually tapped, three or four produced the majority of the sap we collected, and these trees included one ancient maple that is close to Jarvis Gore Drive. It, I suspect, is one of the trees that has survived from those that once lined my road from the intersection of the old "airline" road (Rt.9) along Jarvis Gore Drive often depicted in old photographs from the late nineteenth century. New Englanders often planted a pair of sugar maples in the front of their houses in the old days, and the two identical in size maples near my house may also have been the front of the Unitarian Universalist parsonage in the 1850s that stood on the site of my house which was built in 1879.

We collected roughly 9-10 gallons of sap using old galvanized tin pails with fitted lids and cast-metal spouts borrowed from The Curran Homestead. I filtered the sap thoroughly through four coffee filters set inside of a metal colander. There were moths, bits of bark, and dry sphagnum moss in the sap water before I filtered it. We boiled the sap down in some of my late grandmother’s Presto Pressure Cookers (circa 1950s) on top of our wood stove in the living room. It was a fairly simple process that required a little vigilance to avoid burning the sap down to nothing and scalding the pot with carmelized maple syrup. For the most part, I just set the sap on the stove and checked it when I stoked the fire. I got about 10-11 ounces of dark amber syrup for my efforts that tastes just like the good stuff. I plan on keeping the syrup under lock and key until I can make a pancake and waffle breakfast with it this summer when some of my family comes up to Maine to visit. It will be an exercise in self restraint to save the syrup that long; we love pancakes and waffles at our house. My grandmother always said that stuff that you make yourself always tastes better than anything you buy, and she was right.

Excerpt from Memoir of Col. Jonathan Eddy..., by Joseph W. Porter, 1877.

[With a company raised in Mansfield, Massachusetts, and the vicinity, then Captain Eddy marched and later boarded transports with some 70 men and his subordinate and superior officers en route to Fort Cumberland where the following occurred]:

"Oct. 22. [1759] Orders: 'All Sutlers are forbidden to sell any Spirituous Liquors to any of the Garrison this Day. At 12 o'clock to-day 76 great guns were fired, as well for the King's Coronation day as the joyful news of our success at Canady, at which time every officer on the beat of the General met upon the Fort parade and Drank his Majesty's good health, &c., dureing the fireing, after which they sany God save the King; and they, with the whole Garrison who were all assembled, save those on duty and sick, gave three cheers , at which time 20 Gallons of Rum was made in good Toddy and given to the Soldiery. At night about 6 o'clock, from the alarm posts, every man discharged his Firelock three times, except some that did not go off, and then gave three cheers, which with illuminating all the windows in the garrison belonging to the officers, concluded the Day.'"

"Oct. 22. [1759] Orders: 'All Sutlers are forbidden to sell any Spirituous Liquors to any of the Garrison this Day. At 12 o'clock to-day 76 great guns were fired, as well for the King's Coronation day as the joyful news of our success at Canady, at which time every officer on the beat of the General met upon the Fort parade and Drank his Majesty's good health, &c., dureing the fireing, after which they sany God save the King; and they, with the whole Garrison who were all assembled, save those on duty and sick, gave three cheers , at which time 20 Gallons of Rum was made in good Toddy and given to the Soldiery. At night about 6 o'clock, from the alarm posts, every man discharged his Firelock three times, except some that did not go off, and then gave three cheers, which with illuminating all the windows in the garrison belonging to the officers, concluded the Day.'"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)